Japan-India International Symposium: Japan-U.S.-India Relations in a Turbulent World

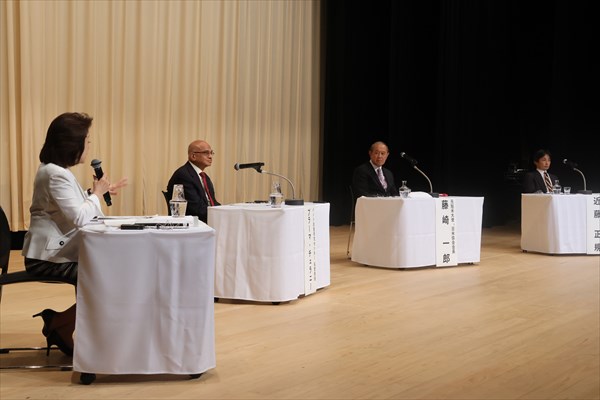

On July 12, 2023, the Japan Institute for National Fundamentals (JINF) hosted the Japan-India International Symposium at Iino Hall in Tokyo. Panelists included keynote speaker Dr. Brahma Chellaney, an Indian geostrategist and professor of strategic studies at the Center for Policy Research based in New Delhi; Former Ambassador of Japan to the United States Ichiro Fujisaki; and Professor Masanori Kondo, Senior Associate Professor at International Christian University and a research fellow at JINF. Facilitated by JINF President Yoshiko Sakurai, the symposium revolved around the theme of “Japan-U.S.-India Relations in a Turbulent World” and focused on the shared regional security threat that is China.

In his keynote speech, Chellaney first explained that competition and conflict between states are inherent due to the anarchic nature of the international political system, namely the lack of a supranational authority to enforce international law and protect the sovereignty of weaker states against more powerful states. “International law is powerful against the powerless, but powerless against the powerful,” he stated. In this realist framework exists the violations of sovereignty seen throughout history, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Although the war in Ukraine has shifted international attention to Europe, Chellaney emphasized that the West’s response to this conflict has brought about significant unintended consequences for the Indo-Pacific region. China is emerging as the ultimate winner from this prolonged fight over the future of Ukraine, while Ukraine, Russia, and the entire Western bloc are weakening. Chellaney cited the Western sanctions against Russia as the driving force behind the deepening Sino-Russian alignment, which has greatly benefited China. This has direct implications for Japanese, Indian, and U.S. security in the Indo-Pacific. For instance, the West turning its back on Russian energy has allowed China to build an “energy safety net” by importing its core energy needs through a land route from Russia, meaning that the West cannot disrupt China’s energy supplies in the case of a Taiwan contingency.

In addition, Chellaney warned that Xi’s invasion of Taiwan will look drastically different from Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Since the mid-1970s, Chinese aggression has been based on three elements: stealth, deception, and surprise. This strategy is evident in China’s approach to both the Senkaku Islands and the border conflict with India. Chellaney believes that China will not conduct a full-force invasion but instead execute a “slow squeeze” of Taiwan or what the U.S. calls the “boiling frog” strategy. This may involve an incremental blockade beginning with the use of civilian militia, among other attempts to isolate Taiwan from the rest of the world. By the time the West notices and coordinates a response, it will be too late.

Next, Fujisaki outlined how we can reconcile with concerns regarding India addressed in American mainstream media, such as India’s participation in both the Quad and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as well as its domestic human rights issues. He explained that we must not overestimate or underestimate India. Recognizing its balanced diplomacy and status as a stable and like-minded democracy, we must strengthen our relationship with India to prevent it from shifting closer to China or Russia.

Kondo then discussed the complexity of Indian foreign policy. India continues its non-aligned, neutral diplomacy despite the war in Ukraine and its worsening relations with China because of the need to maintain its delicate regional balance among Russia, Pakistan, and China, especially as there is a lack of confidence regarding whether the U.S. will come to its rescue if a conflict arises. For example, India has hesitated to align with the West on Russia because Russia supplies 70 percent of India’s weapons and is thus crucial to India’s national security. Kondo also cited the general election next spring as the reason for some of India’s foreign policy decisions, such as its perceived lack of assertiveness against China and its sudden interest in the “Global South.”

Regarding India’s neutral diplomacy, Chellaney provided further context that India has not condemned any previous invasions of sovereign states and the lack of an explicit condemnation does not mean India supports these invasions. India believes that condemnation does not achieve much in diplomacy. He noted that India does not have the capability to be a moral policeman in the first place and is not in the same position as Japan, which is tied to the U.S. by the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty.

So, what should Japan do? Fujisaki proposed building a strong Japan-India network through people-to-people exchanges involving young Japanese and Indian future leaders. Furthermore, while Fujisaki argued that responsible powers cannot remain neutral and must stand up to Russia’s and China’s attempts to change the international order by force, Kondo suggested that Japan, like the U.S., should give up on persuading India to change its foreign policy stance and instead provide support through technology transfer investment and infrastructure projects. Kondo believes that India can be a card against China; thus, a stronger India also benefits Japan.

Chellaney concluded that since the Indo-Pacific region holds the key to the future of international security, Japan, India, and the U.S. must focus on our shared interests and values rather than our differences and cooperate for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific.