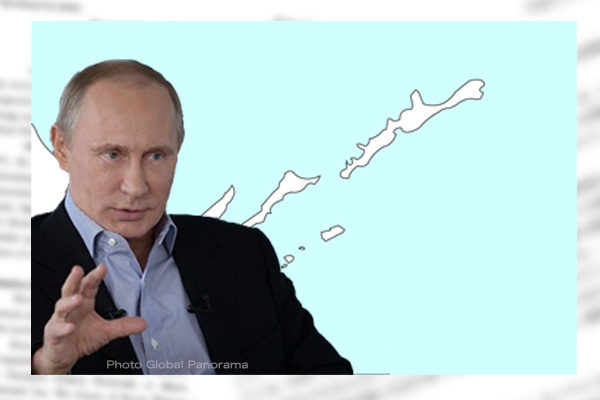

Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny, in which the leader of Wagner private military company in Russia rose against President Vladimir Putin’s government, shook the regime and exposed the weakness of it, though it ended in 24 hours. Given that Russia could plunge into domestic political turmoil due to the unprecedented insurrection in face of a presidential election next March, Japan should shape every option to win back the Russian-occupied Northern Territories with a view to the demise of the Putin regime and the end of the Ukraine war.

Timing is everything in diplomacy

While the Putin regime has cracked down on urban liberals seen as the greatest threat to the president, the Prigozhin mutiny revealed that a greater threat is a non-liberal revolution led by right-wing nationalists. Prigozhin in an SNS message criticized Russian elites for allowing their children to enjoy good living and filming videos in resorts while the children of poor people were dying in the battlefield one after another. As Alexei Navalny, an imprisoned Russian liberal opposition leader, has charged elites with corruption, nationalists have thus come into line with liberals.

Astronomical wealth gaps that have advanced under the Putin regime could be combined with the contradiction of the Ukraine war to trigger social and political unrest.

Whether or not the Putin regime moves toward demise, Japanese diplomacy should be prepared to respond to all possible developments.

While former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker has insisted that timing is everything in diplomacy, Japanese diplomacy vis-a-vis Russia has missed a number of good opportunities, accumulating failures.

President Mikhail Gorbachev of the former Soviet Union made his first visit to Japan in the last year of his presidency, but there was no progress on the Northern Territories issue. Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto negotiated with President Boris Yeltsin of the newborn Russia during Yeltsin’s second term, but the Russian leader’s political base was already weakened.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was eager to conclude a peace treaty with President Putin, but Abe’s efforts failed due to the Putin regime’s transition to a big-power chauvinism.

Japan failing to take advantage of good chances

The biggest postwar chance for Japan to resolve the territorial issue came in 1992 just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Japan’s economic size was 42 times as large as Russia’s. While Russia proposed a flexible solution to the issue in pursuit of economic aid from Japan, the Japanese side ignored the proposal.

The Japanese Foreign Ministry’s poor diplomacy that failed to read trends and aggressively take advantage of good chances could be said as having invited subsequent chaos over the territorial issue.

A new good chance may come with the end of the Putin regime or during a postwar arrangement of the Ukraine war. Unless responses to such event are contemplated now, the failure could be repeated.

The Foreign Ministry reportedly plans to increase the number of diplomats by 20% from the present level to 8,000 by 2030. Unless the ministry achieves progress toward resolving key issues including the Northern Territories issue and North Korea’s abduction of Japanese citizens, it may not get Japanese people’s understanding about the personnel expansion.

Kenro Nagoshi is a specially appointed professor at the Takushoku University, and a former foreign news editor and bureau chief in Moscow, Washington, D.C. and Bangkok for the Jiji Press. He is also a Planning Committee member at the Japan Institute for National Fundamentals.