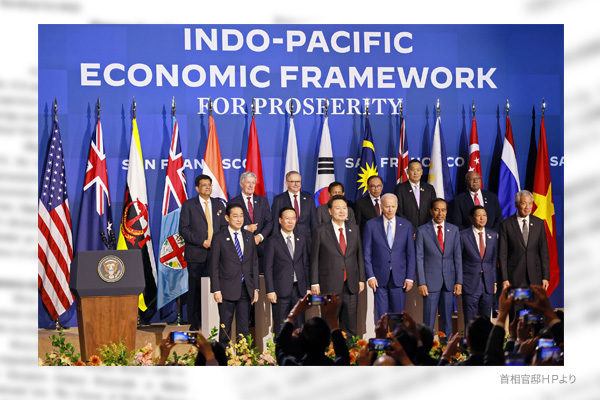

The U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) ministerial and leaders’ meetings took place last week, producing agreement on “decarbonization” and “clean economy” out of the four IPEF pillars, while shelving a deal on “trade.” Last May, the IPEF members agreed on the other pillar, the “enhancement of supply chains.” The above represents achievements in just over a year since the start of negotiations in September 2022. However, this result reflects the U.S. situations in which pillars that can be agreed must be agreed within this year, as the United States will be dominated by the presidential election next year. Regrettably, the examination of the achievements reveals that they are commensurate with the short negotiation period.

Japan led specific initiatives

The key to a successful IPEF is whether the framework can produce practical benefits to win over emerging economies in Asia. The pillars for which IPEF can produce practical benefits are decarbonization and the enhancement of supply chains.

On the support emerging countries’ decarbonization, Japan, the U.S., and Australia will create a $30 million fund. Emerging economies need funding to tackle decarbonization. Therefore, the U.S. and Australia have joined the initiative that Japan alone was trying to implement.

Regarding the enhancement of supply chains, the IPEF members agreed on the establishment of information-sharing networks to support countries facing disruptions to the supply of critical goods. The agreement is also based on an initiative that Japan was trying to implement with emerging Asian economies.

As for the two pillars, Japan has led the development of specific initiatives.

Negative influence of leftist U.S. Democrats

On the other hand, the influence of the U.S. Democrats’ left wing on the Biden administration is dragging down IPEF talks.

Subjected to the negative influence have been talks on the pillar of “fair economy.” The deal on fair economy included measures against money laundering for tax evasion and corruptions that have been requested by the U.S. But emerging economies have no interest in this pillar from the beginning and react tepidly to it.

Regarding “trade,” the U.S. has requested tough standards for protecting workers’ human rights and the environment, which will not increase exports from emerging economies or provide them with practical benefits.

Talks on digital trade rule-making have also come to a standstill. As the movement to regulate giant IT companies is gaining momentum in the U.S. Congress, with the Democratic Party at the center, the rule-making is criticized as only benefitting IT giants, creating a conflict of opinions in the U.S.

A successful IPEF depends on Japan

IPEF is, in the first place, a framework devised by the U.S. to counter China’s growing influence on Asia after withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade agreement. However, since IPEF envisages no tariff elimination or reduction, it is difficult for emerging economies that want to increase exports to the U.S. market to feel practical benefits.

Therefore, unless the U.S. makes efforts to attract Asian emerging economies with some other practical benefits, IPEF will end up only as a slogan. The Biden administration has not only failed to make such efforts but has been dragged down by domestic groups. The U.S. thus depends fully on Japan for a successful IPEF. If a Republican administration comes to power in next year’s presidential election, the U.S. may withdraw from IPEF, as was the case with the TPP. The future of IPEF, which cannot be viewed optimistically, is increasingly dependent on Japan.

Masahiko Hosokawa is a professor at Meisei University and a former director-general of the Trade Control Department at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. He is also a Planning Committee member at the Japan Institute for National Fundamentals.