South Korean government and ruling party have been sending signals seeking to improve relations with Japan. After the prime minister and the National Assembly speaker visited Japan for talks with various people concerned, President Moon Jae In approached Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and had a 10-minute conversation with the Japanese leader at a waiting room before they attended a meeting with leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Bangkok. These developments indicate a turnaround from their summer anti-Japan propaganda urging Korean people to stand against Japan with bamboo spears and remember Admiral Yi Sun Sin who fought against forces sent by then Japanese strong man Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the 16th century.

If Seoul really hopes to improve relations with Tokyo, however, it should start with closed-door, serious negotiations. It should submit specific compromising proposals to resolve a series of pending issues including compensation claims from former wartime Korean workers in Japan, tighter export control on strategic goods and Seoul’s decision to repeal the General Security of Military Information Agreement with Japan. The current South Korean performance without such proposals is designed to develop an impression that serious South Korean efforts to improve relations remain unsuccessful because the Abe government remains too stubborn.

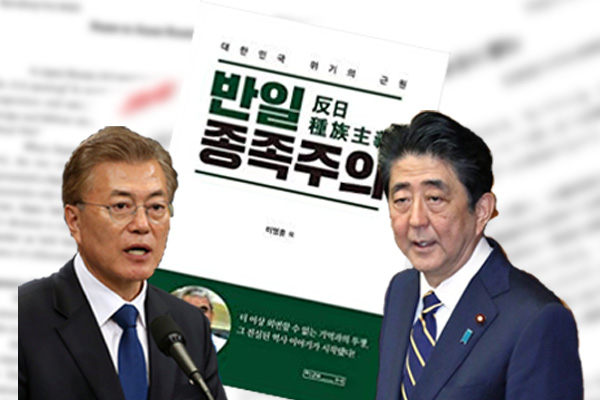

Growing calls against anti-Japan policy in South Korea

The Abe government has consistently asked Seoul to take responsibility to correct a South Korean Supreme Court ruling in October 2018 that ordered a Japanese company to pay compensations to former wartime Korean workers in Japan, contending that the ruling violates international law by reversing bilateral agreements with Japan. The Japanese government has kept its basic stance in response to the Moon regime’s various proposals based on the premise that Japanese firms should bear some costs, demanding that the issue should be resolved within South Korea. The Japanese position is right and legitimate.

This is because calls against anti-Japan policy have grown on an unprecedented scale in South Korea.

In the South Korean academia, former Seoul University professor Lee Yong Hoon and his associates in July authored “Anti-Japan Tribalism,” a book criticizing anti-Japan policy, which has become a best seller selling more than 130,000 copies. In the journalism world, the Munhwa Ilbo newspaper with a nationwide circulation has persistently demanded that the issue of compensations for former wartime Korean workers in Japan be resolved domestically. The Chosun Ilbo newspaper, which had led anti-Japan movements in South Korea, has carried an op-ed that said the South Korean government should not seek compensations from Japan in compliance with the bilateral agreement concerning the settlement of claims issue.

In the political world, three opposition camp lawmakers – two from the Our Republican Party and one from the Liberty Korea Party – delivered short addresses at a symposium attended by Japanese and South Korean conservatives at a National Assembly facility in late September, where Dr. Lee U Yeon and I argued that wartime Korean workers were not forcibly brought or become slave laborers. On November 11, Liberty Korea Party lawmaker Yoon Sang Hyun, who chairs the National Assembly’s Foreign Affairs and Unification Committee, contributed a column to the JoongAng Ilbo newspaper, urging President Moon to declare a vow to refrain from asking Japan to pay compensations to former wartime workers.

Avoid any middle-ground compromise

The only path to improve relations with South Korea is to ally with South Korean conservatives who stand against anti-Japan policy. This is different from a middle-ground compromise that would take into account views of both sides as urged by some senior members of the Japan-South Korea Parliamentarians Union and the Asahi Shimbun newspaper. In the past, there were some South Koreans who argued against anti-Japan policy. For example, Oh Jae Hee, who served as ambassador to Japan between 1991 and 1993, argued that Seoul should believe a Japanese investigation report that there was no evidence of Koreans having been recruited coercively to serve as comfort women. He was fired, after being forced to apologize by even getting down on the knees of former comfort women. Nevertheless, the Japanese government then chose a middle-ground compromise, admitting the coercive recruitment in a 1993 statement by then Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono. Japan should never repeat such mistake.

Tsutomu Nishioka is a senior fellow and a Planning Committee member at the Japan Institute for National Fundamentals and a visiting professor at Reitaku University. He covers South and North Koreas.