On May 10, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection said it blocked Fast Retailing Co.’s Uniqlo brand shirts on concerns they violated a ban on cotton products produced in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region where forced labor has been reported. The case indicates Japanese companies face serious risks due to Western countries’ confrontation with China over human rights abuse.

The Group of Seven industrial democracies are scheduled to hold their trade ministers meeting on May 27 and 28. Britain, this year’s G7 chair, plans to discuss the issue of forced labor. It could enter into resonance with U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai who gives priority to the China human rights issue. Japan may become isolated because of its hesitancy to impose sanctions on China.

The U.S. customs agency published the blocking of Uniqlo shirt imports ahead of the G7 meeting.

Japan should take leadership in making international rules

The Japanese government should not remain hesitant over the human rights issue. Western countries are developing law to require business enterprises to conduct “human rights due diligence” to check procurement sources’ risk of human rights abuse. Japan’s relevant measures have been limited to the preparation of guidelines for companies regarding human rights abuse risks, leaving them to voluntarily decide what to do. This represents a poor showing.

Questioned on the Uniqlo incident, Chief Cabinet Secretary Katsunobu Kato said the government would make adequate efforts to secure legitimate business practices. The problem is how to do so. Free business activities can be restricted in the name of human rights. The problem is that such restrictions could be imposed arbitrarily.

Japan has had a bitter experience regarding business activities restricted in the name of national security. In 1987, Toshiba Machine Co. was alleged to have violated regulations of the COCOM (Coordinating Committee for Export for Communist Areas) as the company’s machine tool exported to the then Soviet Union was suspected of having been used to reduce submarine screw sounds. But it is difficult to check whether exported goods would eventually be used for military purposes. As Japan lacks intelligence capabilities, it has no way to rebut such suspicion.

Japan must have measures to protect its private companies from foreign countries’ arbitrary exploitation of business restrictions. One of such measures is to obtain importers’ pledge not to use imported goods for military purposes. This may be nothing more than a comfort. But any country like Japan should orchestrate an international agreement about minimum requirements for private companies to pave the way for these companies to account for any problems with their business activities.

This is the same case with human rights. It may be almost impossible to check whether the shirts in question were made through forced labor. That’s why the government should aggressively propose to make common international rules that business enterprises should comply with.

Companies’ responses are also precarious

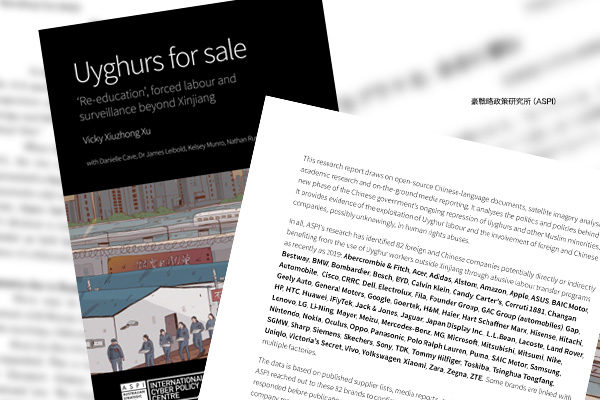

In March 2020, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute published a list of 83 companies suspected of having been involved in deals related to forced labor of Uyghurs, including 14 Japanese firms. The Japanese companies’ responses were mixed. Some conducted investigations or audits about the business connection. Others irrationally produced no response to the enquiry.

At most of Japanese companies, those in charge of corporate social responsibility or procurement divisions are left to make such responses. Only a few companies have held top executive officers responsible for such responses or require these responses to be reported to the board of directors.

However, the human rights problem subject to U.S.-China confrontation is an unprecedentedly serious issue that could shake business management. Japanese companies are now sandwiched between the West and China where they may encounter boycott by the giant market. Business enterprises should fundamentally reform their human rights risk management regime.

Masahiko Hosokawa is a professor at Meisei University and a former director-general of the Trade Control Department at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. He is also a Planning Committee member at the Japan Institute for National Fundamentals.